Ellen van Neerven talks to Indigenous writers Louisa Badayala, Evelyn Araluen Corr, Emma Hicks and Oscar Monaghan

According to Bundjalung educator, Maddee Clark, Indigenous writers write relationally — they are inspired by each other, their writing talks to each other, as well as being in relationship to the land they are from.

According to Bundjalung educator, Maddee Clark, Indigenous writers write relationally — they are inspired by each other, their writing talks to each other, as well as being in relationship to the land they are from.

To discuss the importance of Indigenous writing to the ‘Australian cultural landscape’ is to profile the personal stories of individual writers contributing to the national literature. This October, I’m working with Louisa Badayala, Evelyn Araluen Corr, Emma Hicks and Oscar Monaghan, bringing their diverse ways of working and responding to the upcoming Deadly & Hectic project and Boundless festival in Western Sydney.

In talking about their work, these writers reference writers who are no longer with us and those who are, showing the importance of acknowledging the work of those who have come before — in the genres of life writing, poetry and fiction.

The women in my family are great diary keepers

Louisa Badayala (18) is a young Nyoongar Muslim woman who grew up in Arnhem Land and is living in Perth. Just finished high school, she has already had a short story published in The Big Black Thing, a Sweatshop anthology that came out this year. Her writing is beautiful, conceptual and rooted in family dynamics.

Louisa says she’s inspired by ‘Indigenous women, not just those in the creative fields, but those who work for their communities in all kinds of roles, and show what strength, warmth and perseverance are.’

Early records of Indigenous writing from 1867 include letters from Aboriginal women to the Victorian Board for the Protection of Aborigines, asserting their civil and economic rights and asking to see family members.

Louisa talks about the legacy of writing in her family, ‘The women in my family are great diary keepers. I found one written by a great aunt in the back of a Bible ABC’s book [a book commonly used to teach children the alphabet through the Bible’s characters and settings] the other day, from 1939.’

In choosing to write fiction, Louisa is entering space inhabited by important recent fiction writers such as Tony Birch, Kim Scott, Alexis Wright, Melissa Lucashenko and Tara June Winch.

‘I don’t set out to write the political, but the political finds me. To say the word “Aboriginal” or “Indigenous” is to bring politics into the sphere. To say the word “Muslim” — that’s one of the best buzzwords politics has ever picked up.’

I want to see if there’s anything useful or redeemable about ‘magic realism’

Evelyn Araluen Corr (24) has had a rocket rise since submitting her first poem just 18 months ago. That poem ‘Learning Bundjalung on Tharawal’ went on to place in the 2016 Nakata Brophy Prize for Young Indigenous Writers under 30 and, as the title suggests, traces her language learning journey as a Bundjalung woman on her dad’s side living in Windsor, in Sydney’s west.

Evelyn Araluen Corr (24) has had a rocket rise since submitting her first poem just 18 months ago. That poem ‘Learning Bundjalung on Tharawal’ went on to place in the 2016 Nakata Brophy Prize for Young Indigenous Writers under 30 and, as the title suggests, traces her language learning journey as a Bundjalung woman on her dad’s side living in Windsor, in Sydney’s west.

Her dad is an historian writing about the contact history of the Hawkesbury River. Evelyn is a PhD candidate working with Indigenous literature at the University of Sydney. Her poems have appeared in Cordite, Overland, Rabbit and The Best Australian Poems 2016.

Evelyn is inspired by poets such as Oodgeroo Noonuccal from Quandamooka (North Stradbroke Island) and Ali Cobby Eckermann of Yankunytjatjara/Kokatha (SA) heritage. Oodgeroo Noonuccal is known as a prominent activist and the first Indigenous Australian to publish a book of poetry, We Are Going, in 1964: a bestseller.

This year, Evelyn won the 2017 Nakata Brophy Prize for a short story, ‘Muyum: a transgression’. The story has been described as having magic realist elements, a term used to categorise Gabriel Garcia Marquez and other Latin American writing. This reading is often applied to Indigenous writing that reflects experiences and worldviews that may not fit into a non-Indigenous ‘realism’. Evelyn is continuing to write fiction that unsettles non-Indigenous readers and ways of categorising. ‘I want to see if there’s anything useful or redeemable about [the term].’ She wants to ‘write for black readers and confront white readers’.

Evelyn’s not limited to one genre, and she also uses her black words through social media to advocate, educate and communicate. Evelyn and Louisa met online through Tumblr three years ago, spurred by their similar politics. Evelyn is interested in ‘having these conversations somewhere else’ when they meet in October at Boundless.

I build my language with rocks

Emma Hicks (39) likes going for a run every morning in the bush at the end of her Middle Cove street, in the north of Sydney, where she finds the trees and birds equally arresting, and words and images come together for her. Trained originally as a graphic designer, and also a practising visual artist working across film, installation and performance, her writing is a recent additional form of expression.

She is spurred to tell her grandmother’s story — she was taken from her Kamilaroi Country to the UK where she grew up in an adopted family. Emma’s life writing, highly stylised, fragmented and experimental, follows on from a life writing tradition by Indigenous memoirists Doris Pilkington Garimara, Marie Munkara and Kate Howath. Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence, about Doris Pilkington Garimara’s personal story — one of many about the Stolen Generations’ impact on a family — published in 1997, was a groundbreaker. The film adaption grossed $16 million worldwide and brought the intergenerational impacts on community into the spotlight.

‘My grandmother passed away in 1995 but she continues to give me both inspiration and courage.’ Emma plans on travelling to her grandmother’s country in Rocky Creek in New South Wales soon for the first time. ‘She wrote a lot of poetry.

‘I am thinking a lot about rocks and friendship at the moment. Where I am from, the landscape, it’s rocky and Aboriginal language is responsive to environment. There is a great quote by Édouard Glissant in the Poetics of Relation: Je bâtis à roche mon langage (I build my language with rocks).’

Providing counter-stories to the dominant narratives

While enrolled in a Masters by Research at Sydney Law School, most of Oscar Monaghan (28)’s writing at the moment is around legal history, property law and heteronormativity — though Oscar also writes creative non-fiction and speculative fiction.

While enrolled in a Masters by Research at Sydney Law School, most of Oscar Monaghan (28)’s writing at the moment is around legal history, property law and heteronormativity — though Oscar also writes creative non-fiction and speculative fiction.

It is the combination of law study and an exploration of narratives that reflect diverse sexual and gender orientation that draws comparison to Oscar’s good mate, Gomeroi poet Alison Whittaker, who writes queer rural lives in her collection Lemons in the Chicken Wire, and they both feature in the anthology, Colouring the Rainbow: Blak Queer and Trans Perspectives – Life Stories and Essays.

‘I’m mostly inspired by those I know,’ Oscar says. ‘There’s something about seeing the person behind the work that makes getting work out there into the world seem achievable! For instance, my partner and his approach to creative work (getting it done!) is really inspirational to me. Alison Whittaker, Ellen O’Brien, Eda Gunaydin and Qian Jinghua are incredible sources of inspiration. I am also a big fan of Larissa Behrendt and Nicole Watson — I love their ability to do both legal and creative work!’

Oscar is a descendant of the Guugu Yimithirr people of Far North Queensland, was born on Ngunnawal country (Canberra), and grew up in Cairns. Oscar lives in the inner-west Sydney suburb of Petersham. Indigenous writing means to Oscar, ‘asserting our continued presence and providing counter-stories to the dominant narratives about us and our histories. In doing so, it creates a space for us to see ourselves and to find each other.’

Deadly & Hectic is an exchange between four Indigenous writers and four writers of migrant and refugee backgrounds. This Sweatshop initiative is funded by Create NSW. Writers will perform at the Boundless festival on 28 October. Ellen will be talking with Louisa, Evelyn, Emma and Oscar at the festival.

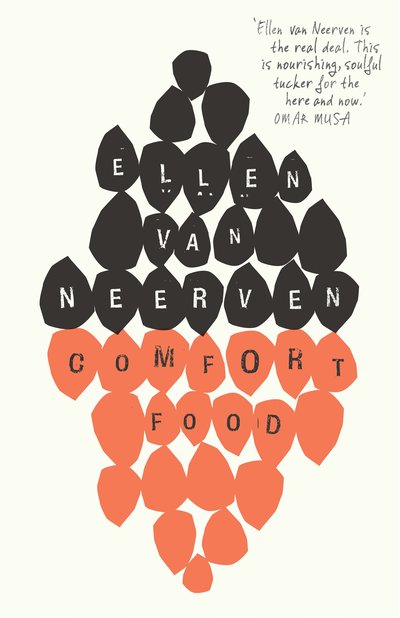

Ellen van Neerven is a young Yugambeh author whose books include Heat and Light and Comfort Food.